Science-Backed Solutions for Better Productivity: The Magic Mind Approach

Unlock Your BrainIntroduction

In modern society, many people are involved in jobs with high cognitive demand and significant information load on a daily basis, prompting the pharmaceutical and supplemental industry to work on effective nootropics to help people to sustain cognitive performance.

Achieving and maintaining optimal performance on demanding tasks while reducing perceived stress levels and increasing energy levels could be of great interest, particularly for population groups with cognitively demanding occupations. Higher levels of psychological stress as measured by the PSS-10 is usually associated with elevated markers of chronic inflammation, suppressed immune function, increased physical & mental fatigue, lowered cognitive function, and reduced work performance (1, 2, 3, 4).

Multiple research studies have confirmed that high perceived chronic stress has a detrimental impact on cognitive functions, not only reducing short-term physical and mental performance and overall quality of life, but also significantly increasing the risk of cognitive impairment and other neurodegenerative conditions in the long run (5, 6). In particular, midlife stress-related exhaustion has been associated with higher risk to develop dementia at a relatively younger age (7). Moreover, those who developed dementia also tended to show persistently lower cognitive functions over years even without dementia. Cognition is a term used to describe the capacity of the brain to process the information as well as acquire and apply knowledge. Cognition usually involves thinking, attention, language, learning, memory and perception (8). Cognitive performance comprises different domains such as sensation, perception, memory, attention & concentration, executive functions, processing speed, and language/verbal skills (9). Cognitive performance depends on complex interplay between the genetics, nutrition, and lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, sleep habits, and stress levels (10).

A growing body of evidence combining both traditional medicinal knowledge and modern scientific research indicates that multiple individual compounds and botanicals can act as nootropics, improving different aspects of brain health such as cognitive performance and psychosocial and emotional status. While the use of nootropics has long been associated with the treatment of cognitive deficits, such as in neurodegenerative conditions, they are currently used by otherwise healthy individuals to improve memory, attention, speed of reaction, motivation, as well as reduce stress level and promote better stress resilience (11).

Nootropic compounds influence cognitive function through a number of mechanisms, including their action on neurotransmitters (dopaminergic, glutamatergic/cholinergic, and serotonergic systems), hormones, and brain signaling pathways and metabolism (12). Given the multifaceted mechanisms of multiple classes of bioactive compounds, supplementation with appropriate combination of multiple herbal extracts and individual compounds should be particularly effective for influencing cognitive function, providing a comprehensive effect. Majority of supplemental dietary nootropics have been investigated in isolation, while studies investigating the effects of a multi-ingredient dietary nootropic on cognitive performance in healthy individuals are limited. We hypothesized that, based on the composition of the supplement Magic MindⓇ and previous studies exploring the effectiveness of the same individual ingredients or their partial combinations, the chronic ingestion of dietary multi-ingredient nootropic could enhance cognitive performance in healthy young adults while reducing stress and improving energy levels. Thus, the main aim of the study was to examine the chronic effect of a dietary multi-ingredient nootropic supplement on stress, anxiety, attention, energy & fatigue, and work productivity and performance in young healthy adults.

-

Study Objectives

To assess the efficacy and impact of the supplement product Magic MindⓇ on stress, anxiety, attention, energy & fatigue, and work productivity and performance.

-

Methods

A retrospective survey was conducted to assess the impact of a supplement product Magic Mind on the measures of stress, anxiety, energy & fatigue, as well as work productivity & performance levels by administering a validated questionnaire for each target area at baseline (Day 0, beginning of the study) as well as on Day 30 and Day 60 of using Magic Mind. Eighty two participants completed the survey at those three timepoints and the results were then used for statistical analysis.

-

A retrospective survey was conducted to assess the impact of a supplement product Magic Mind on the measures of stress, anxiety, energy & fatigue, as well as work product.

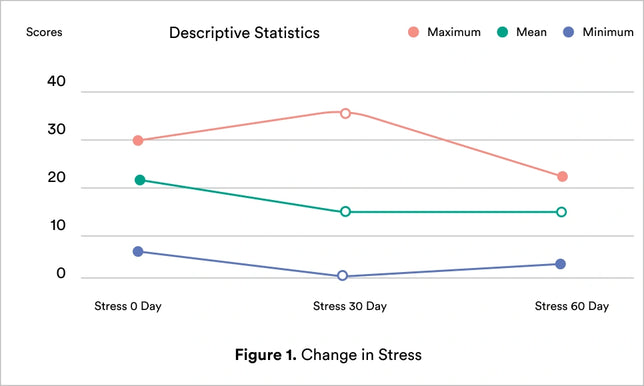

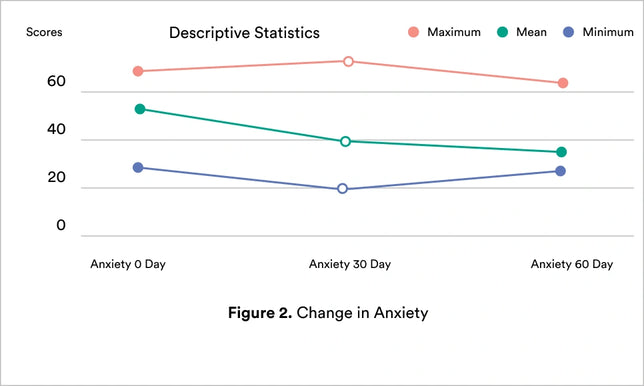

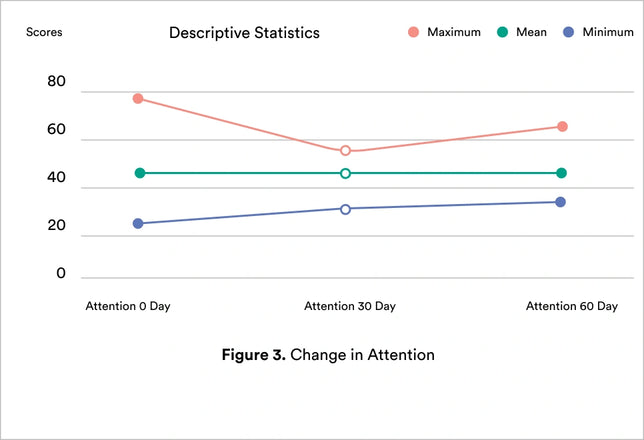

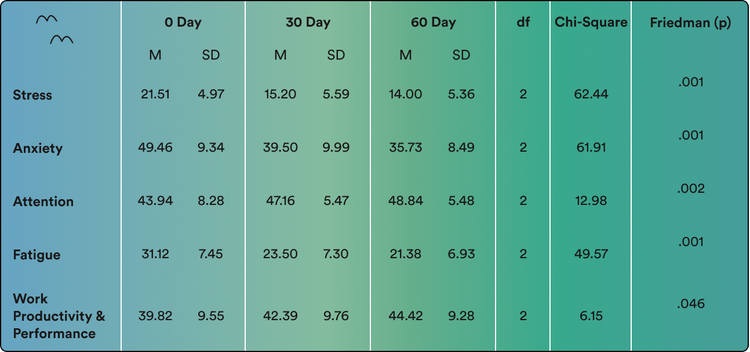

All 82 individuals who completed the present research provided appropriate data. Significant differences were identified between the 0-day, 30-day, and 60-day assessments in terms of stress (p <.001), anxiety (p < .001), attention (p < .001), fatigue (p < .001), and work productivity & performance (p< .046) throughout the study (Table 1).

Analyzing the percentage changes in the variables reveals that, based on the participants' mean scores, there is a 34.9% reduction in stress levels, a 28% decrease in anxiety levels, an 11.5% enhancement in attention, a 31.3% decrease in fatigue levels, and an 11.6% improvement in work productivity and performance. The outcomes also indicated that 57 (69.5%) of the participants had a lower level of stress, 67 (82%) of them had a lower level of anxiety, 36 (44%) of them reported improved attention, 67 (81.7%) of them had lower fatigue, and 41 (50%) of the participants had higher work productivity & performance by the end of the study.

-

Conclusion

Supplementation with Magic MindⓇ was found to be effective in all tested parameters, producing statistically significant decrease in stress and anxiety levels, improvement in energy and attention levels, and increased work productivity & performance.

Measures

The survey administered during the study consisted of validated questionnaires for each particular

- Work productivity

- Anxiety

- Performance

- Stress

- Energy & fatigue

- Focus

-

Which is a robust and widely used instrument for assessing the appraisal of stress. PSS-10 consists of 10 questions with responses varying from 0 to 4 (0 = never; 1 = almost never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = fairly often; 4 = very often), hence a minimum total score of 0 and a maximum total score of 40. The questionnaire included the following questions.

1. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?

2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?

3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?

4. In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?

5. In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way?

6. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?

7. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life?

8. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things?

9. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control?

10. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

The process of calculating the total score included reversing the scores for questions 4, 5, 7, and 8 in the following way: 0=4, 1=3, 2=2, 3=1, 4=0. The total score between 0 and 13 indicated low stress, between 14 and 26 indicated moderate stress, and between 27 and 40 indicated high stress levels. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which is a measure of internal consistency reliability, with a value >.70 considered a minimum measure of internal consistency, was computed to assess the internal consistency of the stress questionnaire and was found to be .87. According to the most comprehensive review of the validity of PSS-10, Cronbach's alpha of the PSS-10 was evaluated at >.70 in all 12 studies in which it was used(13).

-

With 20 questions ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = almost always), with the scores for items 1, 6, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19 being reverse-scored (4 = almost never, 3 = sometimes, 2 = often, 1 = almost always), hence a minimum score of 20 and a maximum score of 80

The questionnaire included the following statements:

1. I feel fine. 2. I tire quickly. 3. I feel like crying. 4. I wish I could be as happy as others seem to be. 5. I am losing opportunities because I cannot make decisions fast. 6. I feel rested. 7. I feel calm. 8. I feel that difficulties are piling up in such a way that I cannot overcome them. 9. I worry too much about things that do not really matter. 10. I am happy. 11. I am inclined to take things hard. 12. I lack self-confidence. 13. I feel secure. 14. I try to avoid facing a crisis or difficulty. 15. I feel blue. 16. I am content. 17. Some unimportant thoughts run through my mind and bother me. 18. I take disappointments so keenly that I cannot get them out of my mind. 19. I am a steady person. 20. I become tense and upset when I think about my current concerns

The process of calculating the total score included reversing the scores for questions 1, 6, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to evaluate the internal consistency of the anxiety questionnaire, yielding a satisfactory value of .90

-

Which is a self-report scale that is designed to measure two major components of attention, attention focusing and attention shifting.

The ATTC has 20 items that are rated on a four-point likert scale:

1 = almost never;

2 = sometimes;

3 = often;

4 = always

For items 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 20, the results were reverse-scored:

4 = almost never;

3 = sometimes;

2 = often;

1 = always

The questionnaire included the following statements- It’s very hard for me to concentrate on a difficult task when there are noises around.

- When I need to concentrate and solve a problem, I have trouble focusing my attention.

- When I am working hard on something, I still get distracted by events around me.

- My concentration is good even if there is music in the room around me.

- When concentrating, I can focus my attention so that I become unaware of what’s going on in the room around me.

- When I am reading or studying, I am easily distracted if there are people talking in the same room.

- When trying to focus my attention on something, I have difficulty blocking out distracting thoughts.

- I have a hard time concentrating when I’m excited about something.

- When concentrating I ignore feelings of hunger or thirst.

- I can quickly switch from one task to another.

- It takes me a while to get really involved in a new task.

- It is difficult for me to coordinate my attention between the listening and writing required when taking notes during lectures.

- I can become interested in a new topic very quickly when I need to.

- It is easy for me to read or write while I’m also talking on the phone.

- I have trouble carrying on two conversations at once.

- I have a hard time coming up with new ideas quickly.

- After being interrupted or distracted, I can easily shift my attention back to what I was doing before.

- When a distracting thought comes to mind, it is easy for me to shift my attention away from it.

- It is easy for me to alternate between two different tasks.

- It is hard for me to break from one way of thinking about something and look at it from another point of view.

The internal consistency of the attention questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which yielded an adequate result of 0.83. The recent studies also found that ATTC may be used as a valid and reliable instrument for assessment of two subdomains of attention, focusing and shifting, as its satisfactory internal consistency and discriminant validity have been confirmed in studies (14). The reported internal consistency of ATTC is α = 0.88 (15). -

With each item of the FAS having answers at a five-point, Likert-type scale: ranging from 1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = regularly; 4 = often, 5 = always. Items 4 and 10 are reverse-scored. Total scores can range from 10, indicating the lowest level of fatigue, to 50, indicating the highest level of fatigue.

The questionnaire included the following statements:

1. I am bothered by fatigue

2. I get tired very quickly

3. I don't do much during the day

4. I have enough energy for everyday life

5. Physically, I feel exhausted

6. I have problems starting things

7. I have problems thinking clearly

8. I feel no desire to do anything

9. Mentally, I feel exhausted

10. When I am doing something, I can concentrate quite wellThe reported internal consistency of FAS has been determined between 0.83 - 0.90 (16, 17).

-

The questionnaire consists of 18 questions divided into two parts, with the answers ranging from 0 to 4 for part 1 (0 = seldom; 1 = occasionally; 2 = sometimes; 3 = regularly; 4 = always) and from 0 to 4 for part 2 (0 = never; 1 = seldom; 2 = sometimes; 3 = regularly; 0 = often), hence the minimum score of 0 and the maximum score of 72.

The questionnaire included the following statements:

Part 1:

1. I managed to plan my work so that I finished it on time

2. I kept in mind the work result I needed to achieve

3. I was able to set priorities

4. I was able to carry out my work efficiently

5. I managed my time well

6. On my own initiative, I started a new task when my old tasks were completed

7. I took on challenging tasks when they were available

8. I worked on keeping my job-related knowledge up-to-date

9. I worked on keeping my work skills up-to-date

10. I came up with creative solutions for new problems

11. I took on extra responsibilities

12. I continually sought new challenges in my work

13. I actively participated in meetings and/or consultationsPart 2:

1. I complained about minor work-related issues at work

2. I made problems at work bigger than they were

3. I focused on the negative aspects of situation at work instead of the positive aspects

4. I talked to colleagues about the negative aspects of my work

5. I talked to people outside the organization about the negative aspects of my workThe internal consistency of IWPQ was evaluated by using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which produced a satisfactory value of 0.88. Previously, studies that used IWPQ have shown good internal consistency for task performance (α = 0.78), contextual performance (α = 0.85) and counterproductive work behavior (α = 0.79) (18).

Statistical Analysis

The analyses were conducted by using SPSS (the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) To assess the impact of supplement items on stress, anxiety, attention, fatigue, work productivity & performance levels on 0 day, 30 day and 60 day intervals. Prior to conducting any statistical analysis, the data was examined for data input and assessed for normality, including skewness.

The non-parametric data was evaluated using a Friedman test for K-related samples due to its departure from a normal distribution. In order for data to be considered statistically significant, the chance of type I error was accepted to be less than .05 percentage points

Results

The non-parametric K related samples test, as well as the Friedman Test, were used to assess the enhancement achieved after conducting surveys at 0, 30, and 60 day intervals in order to determine the effect of supplement products on stress, anxiety, attention, fatigue, and work productivity & performance levels of the participants.

Table 1.

Outcomes for Stress, Anxiety, Attention, Fatigue, and Work Productivity & Performance at 0 Day 0, Day 30, and Day 60 of supplementation (N=82)

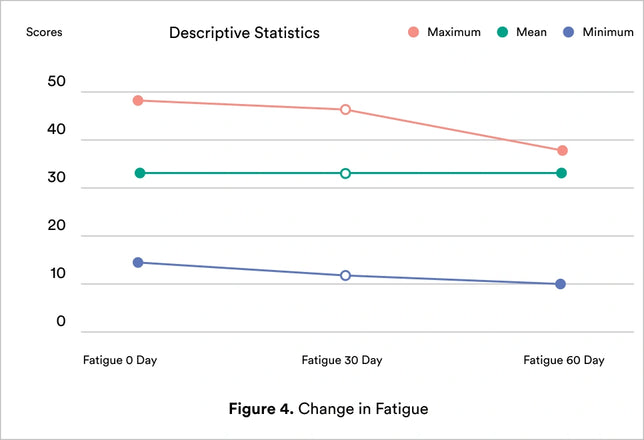

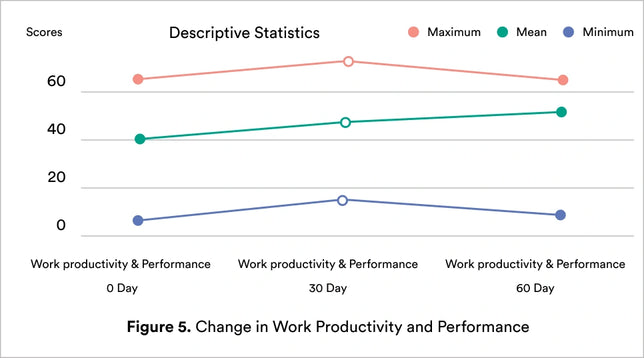

All 82 individuals who completed the present research provided appropriate data. Significant differences were identified between the 0-day, 30-day, and 60-day assessments in terms of stress (p < .001), anxiety (p < .001), attention (p < .001), fatigue (p < .001), and work productivity & performance (p < .046) throughout the study (Table 1). Analyzing the percentage changes in the variables reveals that, based on the participants' mean scores, we observed a 34.9% reduction in stress levels, a 28% decrease in anxiety levels, an 11.5% enhancement in attention, a 31.3% decrease in fatigue levels, and an 11.6% improvement in work productivity and performance.

Besides, in order to further enhance the numerical output, the difference between mean values for 0, 30, and 60 days was compared using a graphical analysis of the report (Figures 1-5).In particular, the outcomes indicated that 57 (69.5%) of the participants had a lower level of stress, 67 (82%) of them had a lower level of anxiety, 36 (44%) of them reported improved attention, 67 (81.7%) of them had lower fatigue, and 41 (50%) of the participants had higher work productivity & performance by Day 60.

Magic MindⓇ formula represents a synergistic blend of ingredients that target mental health & performance. In particular, the key ingredients of the formula include Organic Ceremonial Grade Matcha, Ashwagandha, Bacopa monnieri, CognizinⓇ Citicoline, Rhodiola rosea, cordyceps, lion's mane, L-theanine, organic natural caffeine, turmeric, vitamins B2, B3, B12, and D3, and vitamin C.

Ingredients Backed by Science

The study found the multi-ingredient formula of Magic MindⓇ was effective in all tested parameters, producing:

1) A decrease in stress and anxiety levels;

2) Improvements in energy and attention levels;

3) A subsequent increase in work productivity & performance.

To date, multiple studies have shown the beneficial effects of these ingredients on mental health and performance, including stress levels, anxiety, depressive symptoms, attention & focus, physical and mental fatigue, and work productivity, either in combination or alone.

-

Lion's mane is a medicinal herb with notable neuroprotective and antioxidant properties. The main bioactive compounds of lion's mane, hericenones and erinacines, have been shown to stimulate the synthesis of nerve growth factor (NGF)(61). Due to this, lion's mane is usually used for improving cognitive function in both healthy individuals and patients with cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative disorders. A systematic evaluation of the effects of medicinal mushrooms on mood and cognition has found significant improvements in almost all clinical trials that used lion's mane(62), with the statistically robust cognitive benefits especially in middle-aged and older adults. Favorable changes in scores of neurocognitive and behavioral assessments were attributed to changes in structure and connectivity of neuronal tissue. The mechanisms behind lion's mane health effects include its ability to reduce formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increase the levels of antioxidant enzymes; lion's mane is also capable of decreasing pro-inflammatory markers and markers of neuronal damage, thus improving brain health. Due to this, lion's mane exhibits both neuroprotective and neurotrophic activity(63).

-

Cordyceps is a parasitic fungus with a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine. Cordyceps is often used for a purpose of improving physical and mental resilience to stress, improve overall performance, and promote vitality and longevity. Cordyceps is likely to have a notable effect on stress & fatigue. One animal study has shown that hot water extract of cordyceps reduces fatigue during swimming tests and lowers biochemical markers of stress(56).A few studies in humans have also confirmed anti-fatigue effects of cordyceps(57,58). Active constituents of cordyceps are polysaccharides, adenosine, cordycepin, cordycepic acid, and ergosterol, which are also partially responsible for its anti-inflammatory and immune-boosting properties(59,60).

-

Bacopa monnieri is a popular nootropic herb that has been traditionally used for cognitive enhancement and promoting longevity. It may also relieve anxiety and stress and improve general vitality (36). The most likely mechanisms behind Bacopa's health benefits include its interaction with the dopamine, serotonin, and cholinergic systems; it may also improve neuronal communication via increased growth of dendrites. It could also have anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (37). Bacopa monnieri may also reduce cortisol secretion and prevent depletion of dopamine and serotonin, thus alleviating the negative effects of chronic stress (38). According to clinical studies, supplementation with Bacopa monnieri supports mood and motivation, improves working memory, and enhances mental clarity and cognitive functioning.

For example, a 12-week study in healthy volunteers has shown that supplementation with Bacopa improved objective measures of attention, cognitive processing and working memory mainly via suppression of the activity of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which prevents acetylcholine degradation. The results were significant for both 300 mg/day and 600 mg/day groups (39). Studies also suggested that Bacopa may reduce the rate of forgetting of newly acquired information, improving information retention and memory consolidation (40, 41). A recent, triple-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effects of Bacopa monnieri supplementation in patients with mild cognitive impairment has found that Bacopa can improve attention and verbal fluency as well as potentially reduce the rate of language and attention decline in early stages of dementia, and the effect is more pronounced with longer duration of supplementation (42). In addition, the most recent systematic review of neuroprotective and cognitive-enhancing effects of Bacopa monnieri reinforced its beneficial role in brain disorders, including hyperactivity, depression, attention deficit, learning problems, memory retention, impulsivity, and psychiatric problems due to Bacopa's role in improving neuronal regeneration and transmission (43).

-

Curcuma longa, usually known as turmeric, is a plant of the ginger family. The main constituents of turmeric with notable bioactive properties are curcumin and curcuminoids. In particular, they have a strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (80). Due to this, curcumin has been studied for a variety of health conditions and diseases (81, 82). Curcumin may act as a potent antidepressant by influencing balance of neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline and glutamate), and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis functioning.

It can also target immune pathways, regulate inflammation, and reduce oxidative stress and mitochondrial disturbances. Furthermore, curcumin has been shown to increase levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which plays a role in neurogenesis, thus improving neuronal connectivity and overall brain functioning (83). A recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that curcumin may improve working memory and processing speed, most likely by reducing inflammation and inhibiting pro-inflammatory NFκB and TNF-α to reduce reactive oxygen species (84). In a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, supplementation with curcumin for 18 months has been shown to improve attention and memory, with the effect being attributed mostly to the ability of curcumin to reduce accumulation of beta-amyloid and tau protein in the brain areas that are involved in memory processing (85).

-

Rhodiola is a medicinal herb that is widely used as an adaptogen (48). While the mechanisms of action of rhodiola are not fully understood, research suggests that it has a significant effect on lowering stress at the cellular and systemic levels.

Although rhodiola is primarily used for its fatigue- and stress-reducing properties, it also has antidepressant and anti-inflammatory properties (49, 50, 51). Animal studies have shown that rhodiola likely influences multiple cellular signaling mechanisms associated with stress response, particularly by preventing excessive cortisol release (52). Clinical studies have shown that rhodiola can be especially effective for increasing mental performance under stressful conditions.

For example, a 4-week rhodiola supplementation showed clinically relevant improvements on all seven tests with regard to stress symptoms (53). A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials has found that both acute and chronic supplementation with rhodiola reduces cognitive fatigue, processing errors and reaction time, and improves sustained attention and general well-being (54). Some preliminary evidence also suggests that rhodiola also has anxiolytic properties. In an open-label clinical trial, supplementation with rhodiola reduced subjective measures of anxiety in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (55).

-

Ashwagandha is the most well-known Ayurvedic herb often used for reducing stress and anxiety. However, it has a wide range of other beneficial properties: ashwagandha may increase testosterone levels, promote reproductive function, enhance physical performance, and improve immunity. Ashwagandha is rich in numerous bioactive compounds, but withanolides are thought to be responsible for most of its benefits, which include anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and cardioprotective properties (26).

Ashwagandha is considered to be an adaptogen, thus promoting resilience to stress factors. A strong body of evidence supports anxiolytic and stress-relieving properties of ashwagandha. Multiple studies have confirmed the role of ashwagandha in reducing anxiety in both healthy individuals and patients with generalized anxiety disorder, including being a safe and effective adjunctive therapy to antidepressant medications (27, 28, 29). It's thought that many of the stress-related benefits of ashwagandha are tied to its influence on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, particularly to its ability to regulate cortisol levels (30). Due to the individual variation in HPA axis activity and susceptibility to stress, the magnitude of the effect of ashwagandha will also vary considerably. Numerous clinical studies confirmed that a strong cortisol-lowering effect of ashwagandha translates into better health outcomes in anxiety, sleep issues, cognitive functioning, fertility, and even weight management (31, 32, 33, 34, 35).

-

Theanine is a nonprotein amino acid that is chemically similar to glutamic acid. L-theanine is one of the important constituents of green tea and partially responsible for its health benefits. L-theanine has a wide range of health benefits, acting as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, anticancer, and cardio-, liver and kidney protective compound(64).In terms of cognitive functioning, L-theanine is known to reduce anxiety and stress and improve mental performance. Such effects can be explained by the ability of L-theanine to quickly cross the blood-brain barrier after consumption, promoting increased alpha-wave activity, which is a type of brain waves associated with a more relaxed state(65,66). In general, supplementation with L-theanine has been shown to improve attention, executive function, and memory(67,68,69). The recent study has shown that a 28-day supplementation of L-theanine significantly decreased perceived stress and light sleep, improved sleep quality and enhanced cognitive attention(70).The effect of the combination of L-theanine and caffeine has also been researched extensively. Caffeine is a strong stimulant of the central nervous syndrome and can also have less desirable side effects, including anxiety, nervousness, and restlessness, all of which can be diminished by concurrent administration of L-theanine. In addition, the beneficial cognitive effects of L-theanine, such as attention and focus, have been shown to improve with co-administration of caffeine and L-theanine(71,72,73).

-

Citicoline (CDP-choline) is a nootropic compound that serves as a precursor to choline and uridine, both of which confer neuroprotective and cognitive-enhancing properties by helping regulate metabolism of acetylcholine and phospholipids (44).

CognizinⓇ is a patented form of Citicoline with a number of clinical studies that back up its benefits in both healthy individuals and patients with medical conditions, such as traumatic brain injury, glaucoma, and neurodegenerative conditions. In healthy individuals, the main benefits of citicoline include improvements in attention, focus, and memory.

A recent clinical study of supplementation of citicoline for 12 weeks improved overall memory performance, especially episodic memory, in healthy older people both with and without dementia or age-associated memory impairment (AAMI) (45, 46). Citicoline's benefits can also be explained by its ability to improve cellular bioenergetics, particularly by increasing levels of ATP and phosphocreatine in the brain, and to increase formation of neuronal cell membranes (47). Citicoline also seems to have a dopaminergic activity by increasing levels of the dopamine transporter as well as the amount of dopamine released from stimulated neurons. This suggests that citicoline can attenuate the decline in dopamine levels associated with general neurotransmitter imbalances and some neurodegenerative conditions (44).

-

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin with hormone-like activity in the human body. Due to the presence of vitamin D receptors in virtually all body cells, it plays a crucial role in numerous physiological processes, supporting bone health, immunity, mood, and cognitive function, to name a few(98,99). While the positive impact of optimal vitamin D levels for the musculoskeletal system is well-established, its neuroprotective effects are less studied, despite widespread presence of vitamin D receptors in the brain cells. Studies indicate that low vitamin D levels may increase the risk of cognitive decline as its biologically active form plays a role in clearance of amyloid plaques in the brain(100).In addition to antidepressant properties of vitamin D(101),it may also improve work productivity as low vitamin D status is associated with reduced work productivity(102).Low vitamin D concentrations may contribute to higher perceived stress levels(103).Overall, the research supports the association between vitamin D deficiency and psychological stress(104). Moreover, vitamin D deficiency is widespread as the majority of people work and spend most of their daytime indoors(105),which also negatively contributes to mood, stress levels, and work productivity.

-

Vitamin C is the primary water-soluble compound and a vital nutrient with numerous functions in the body, mainly participating in collagen production, synthesis of carnitine and some neuropeptides, and acting as antioxidant. In addition to its primary role in supporting healthy immune function and preventing infectious disorders, vitamin C is also a promising brain nutrient. Vitamin C is concentrated in the brain through a combination of active transport into brain tissue and retention via the blood-brain barrier. Higher plasma vitamin C levels correlate with better cognitive function or lower risk of cognitive decline (106). In a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease, lower levels of vitamin C in the cerebrospinal fluid were found to increase oxidative stress and accelerate amyloid deposition and disease progression, suggesting neuroprotective role of vitamin C (107). In a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, supplementation with vitamin C has been shown to increase work motivation and attentional focus. Overall, vitamin C may improve mental vitality, a combined measure assessed by measuring fatigue, attention, work engagement, stress, depression, and anxiety (108). In general, the overall body of evidence from the systematic reviews and cross-sectional studies support the idea that higher vitamin C concentrations may promote better cognitive function, improving performance on tasks involving attention, focus, working memory, and decision speed (109, 110).

In addition to numerous direct cognitive-enhancing effects of the ingredients mentioned above, they also improve mental health & performance indirectly, particularly by influencing gut microbiome composition. For instance, matcha has been found to modulate the gut microbiome composition due to its rich content of catechins and insoluble dietary fiber, resulting in increased beneficial beneficial Coprococcus and a decrease of potential pathogenic Fusobacterium in the gut microbiota (111).However, the reverse is also true as stress-reducing effect of matcha can also trigger favourable changes in gut microbiota. The antioxidant compounds in matcha, such as EGCG, can reduce inflammatory processes in the gut, thus promoting better mental health via gut-brain connection (112). Another study revealed that EGCG can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria like Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium dif icile while increasing the abundance of beneficial Bifidobacterium spp. and Akkermansia spp (113).The anti-depressant effect of Bacopa monnieri could partially be explained by modulation of the gut microbiome as well (114).

The anti-fatigue effects of bioactive compounds of Rhodiola, such as salidrosides, are likely to be modulated via their influence on gut microbiome composition (115). Active compounds of Lion’s mane act as prebiotics, improving gut microbiota, which modulates brain function by reducing the risk of neuroinflammation, according to animal and human studies (116, 117). Lastly, vitamin D has a pleiotropic effect on gastrointestinal functioning by affecting both gut microbiome and resident immune cells, thus shaping gut microbiome composition and helping maintain the integrity of intestinal mucosal barrier (118). Considering the role of gut microbiota in production of neurotransmitters, vitamins, and other beneficial metabolites, it’s important to target microbiome composition with natural ingredients that help restore healthy microbiome balance

-

Ceremonial grade matcha is a type of matcha used in traditional Japanese tea ceremonies. Ceremonial grade matcha usually offers high quality compared to culinary grade matcha. Matcha has long been used in Asian countries, particularly Japan, due to its higher concentrations of bioactive compounds than in other types of green tea, particularly due to the unique farming and harvesting process.

Match contains a unique combination of theanine, catechins, and caffeine, which particularly defines the quality of the green tea. Matcha also provides a high level of “umami” flavor profile which can be explained by its high content of amino acids. Overall, 60-70% of insoluble ingredients in matcha are represented by fat-soluble vitamins, insoluble dietary fibers, chlorophylls, and proteins, while the rest is made of polyphenols, water-soluble vitamins, caffeine, minerals, dietary fibers, and amino acids (19). Due to being a significantly more concentrated form of green tea, match has a much higher antioxidant content.

Polyphenols account for up to 30% of matcha’s dry weight with 90% of those being catechins. One of the most abundant and bioactive is epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) (20). To date, there have been a number of studies showing a wide range of health benefits of matcha in various health domains, including cardiovascular health, metabolic function, and cognitive performance. For example, studies have shown that continuous matcha intake alongside caffeine can improve attention, executive function, and work performance compared to caffeine alone (21).

Moreover, the same study also showed that continuous intake of matcha led to an enhanced performance under increased stress load compared to caffeine, emphasizing the beneficial effect of regular, long-term matcha use. Matcha intake also significantly reduces anxiety and stress levels (22). The brain is especially vulnerable to oxidative stress, and the majority of beneficial cognitive effects of matcha can be attributed to antioxidant content of matcha, particularly EGCG. Bioactive compounds in matcha, including caffeine and catechins, improve dopaminergic and cholinergic transmissions in the brain (23, 24). EGCG has been shown to reduce neuroinflammation in the hypothalamic microglial cells, which lowered the risk for cognitive decline (25).

Conclusion

Supplementation with Magic MindⓇ was found to be effective in all tested parameters. Participants experienced statistically significant decrease in stress and anxiety levels, improvement in energy and attention levels, and increased work productivity & performance. The tested formula has been shown to be effective in improving cognitive performance while reducing the levels of perceived stress as well as physical and mental fatigue. Overall, the study outlined the benefits of natural dietary supplementation for promoting better mental health and performance. Studies with longer duration and further research with a control group are needed to understand the long-term effects of multi-ingredient supplement formula Magic MindⓇ on physical & mental health and performance and to confirm these findings.

References

1. Munoz E, Sliwinski MJ, Scott SB, Hofer S.

Global perceived stress predicts cognitive change among older adults. Psychol Aging.2015;30(3):487-499. doi:10.1037/pag0000036

2. James KA, Stromin JI, Steenkamp N, Combrinck MI.

Understanding the relationships between physiological and psychosocial stress, cortisol and cognition. Front Endocrinol(Lausanne). 2023;14:1085950. Published 2023 Mar 6. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1085950

3. Mariotti A. The effects of chronic stress on health:

new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain-body communication. Future Sci OA. 2015;1(3):FSO23. Published 2015 Nov 1. doi:10.4155/fso.15.21

4. Bui T, Zackula R, Dugan K, Ablah E.

Workplace Stress and Productivity: A Cross-Sectional Study. Kans J Med. 2021;14:42-45. Published 2021 Feb 12. doi:10.17161/kjm.vol1413424

5. Arifi D, Bitterlich N, von Wolff M, Poethig D, Stute P.

Impact of chronic stress exposure on cognitive performance incorporating the active and healthy aging (AHA) concept within the cross-sectional Bern Cohort Study 2014(BeCS-14). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(4):1021-1032. doi:10.1007/s00404-021-06289-z

6. Bisht K, Sharma K, Tremblay MÈ.

Chronic stress as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: Roles of microglia-mediated synaptic remodeling, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;9:9-21. Published 2018 May 19. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.05.003

7. Guo X, Hällström T, Johansson L, et al.

Midlife stress-related exhaustion and dementia incidence: a longitudinal study over 50 years in women. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):500. Published 2024 Jul 11. doi:10.1186/s12888-024-05868-z

8. Dhakal A, Bobrin BD. Cognitive Deficits. In:

StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; February 14, 2023.

9. Harvey PD. Domains of cognition and their assessment.

Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21(3):227-237. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.3/pharvey

10. Dominguez LJ, Veronese N, Vernuccio L, et al.

Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Other Lifestyle Factors in the Prevention of Cognitive Decline and Dementia. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4080. Published 2021 Nov 15. doi:10.3390/nu13114080

11. Roe AL, Venkataraman A.

The Safety and Efficacy of Botanicals with Nootropic Effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(9):1442-1467. doi:10.2174/1570159X19666210726150432

12. Suliman NA, Mat Taib CN, Mohd Moklas MA, Adenan MI, Hidayat Baharuldin MT, Basir R. Establishing Natural Nootropics:

Recent Molecular Enhancement Influenced by Natural Nootropic. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:4391375. doi:10.1155/2016/4391375

13. Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale.

Asian Nurs Res(Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2012;6(4):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

14. Townshend K, Bornschlegl M. Attention Control Scale(ACS).

Springer eBooks. Published online January 1, 2024:1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77644-2_85-1

15. Derryberry D, Reed MA.

Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):225-236. doi:10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225

16. Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL.

Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(4):345-352. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00392-6

17. Bråndal A, Eriksson M, Wester P, Lundin-Olsson L.

Reliability and validity of the Swedish Fatigue Assessment Scale when self-administrered by persons with mild to moderate stroke.

Top Stroke Rehabil. 2016;23(2):90-97. doi:10.1080/10749357.2015.1112057

18. Koopmans L, Coffeng JK, Bernaards CM, et al.

Responsiveness of the individual work performance questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:513. Published 2014 May 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-513

19. Maeda-Yamamoto M, Tachibana H, Sameshima Y, Kuriyama S. Green Tea (Cv. Benifuuki) Powder and Catechins Availability. In:

Academic Press; 2012:115-125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384937-3.00010-0

20. Kochman J, Jakubczyk K, Antoniewicz J, Mruk H, Janda K.

Health Benefits and Chemical Composition of Matcha Green Tea: A Review. Molecules. 2020;26(1):85. Published 2020 Dec 27. doi:10.3390/molecules26010085

21. Baba Y, Inagaki S, Nakagawa S, Kobayashi M, Kaneko T, Takihara T.

Effects of Daily Matcha and Caffeine Intake on Mild Acute Psychological Stress-Related Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1700. Published 2021 May 17. doi:10.3390/nu13051700

22. Unno K, Furushima D, Hamamoto S, et al.

Stress-Reducing Function of Matcha Green Tea in Animal Experiments and Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1468. Published 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/nu10101468

23. Sakurai K, Shen C, Ezaki Y, et al.

Effects of Matcha Green Tea Powder on Cognitive Functions of Community-Dwelling Elderly Individuals. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3639. Published 2020 Nov 26. doi:10.3390/nu12123639

24. Kim JM, Lee U, Kang JY, Park SK, Kim JC, Heo HJ.

Matcha Improves Metabolic Imbalance-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:8882763. Published 2020 Nov 28. doi:10.1155/2020/8882763

25. Zhou J, Lin H, Xu P, et al.

Matcha green tea prevents obesity-induced hypothalamic inflammation via suppressing the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2020;11(10):8987-8995. doi:10.1039/d0fo01500h

26. Paul S, Chakraborty S, Anand U, et al.

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha): A comprehensive review on ethnopharmacology, pharmacotherapeutics, biomedicinal and toxicological aspects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;143:112175. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112175

27. Pratte MA, Nanavati KB, Young V, Morley CP.

An alternative treatment for anxiety: a systematic review of human trial results reported for the Ayurvedic herb ashwagandha(Withania somnifera). J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(12):901-908. doi:10.1089/acm.2014.0177

28. Fuladi S, Emami SA, Mohammadpour AH, Karimani A, Manteghi AA, Sahebkar A.

Assessment of the Efficacy of Withania somnifera Root Extract in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Double-blind Placebo- Controlled Trial. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2021;16(2):191-196. doi:10.2174/1574884715666200413120413

29. Salve J, Pate S, Debnath K, Langade D. Adaptogenic and Anxiolytic Effects of Ashwagandha Root Extract in Healthy Adults:

A Double-blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Clinical Study. Cureus. 2019;11(12):e6466. Published 2019 Dec 25. doi:10.7759/cureus.6466

30. Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Drummond PD. Modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by plants and phytonutrients:

a systematic review of human trials. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(8):1704-1730. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2021.1892253

31. Remenapp A, Coyle K, Orange T, et al.

Efficacy of Withania somnifera supplementation on adult's cognition and mood. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2022;13(2):100510. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2021.08.003

32. Gopukumar K, Thanawala S, Somepalli V, Rao TSS, Thamatam VB, Chauhan S. Efficacy and Safety of Ashwagandha Root Extract on Cognitive Functions in Healthy, Stressed Adults:

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:8254344. Published 2021 Nov 30. doi:10.1155/2021/8254344

33. Mahdi AA, Shukla KK, Ahmad MK, et al.

Withania somnifera Improves Semen Quality in Stress-Related Male Fertility. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. Published online September 29, 2009. doi:10.1093/ecam/nep138

34. Lopresti AL, Drummond PD, Smith SJ. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study Examining the Hormonal and Vitality Effects of Ashwagandha ( Withania somnifera) in Aging, Overweight Males.

Am J Mens Health. 2019;13(2):1557988319835985. doi:10.1177/1557988319835985

35. Choudhary D, Bhattacharyya S, Joshi K.

Body Weight Management in Adults Under Chronic Stress Through Treatment With Ashwagandha Root Extract: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(1):96-106. doi:10.1177/2156587216641830

36. Sukumaran NP, Amalraj A, Gopi S.

Neuropharmacological and cognitive effects of Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst - A review on its mechanistic aspects. Complement Ther Med. 2019;44:68-82. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2019.03.016

37. Basheer A, Agarwal A, Mishra B, et al.

Use of Bacopa monnieri in the Treatment of Dementia Due to Alzheimer Disease: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Interact J Med Res. 2022;11(2):e38542. Published 2022 Aug 1. doi:10.2196/38542

38. Brimson JM, Brimson S, Prasanth MI, Thitilertdecha P, Malar DS, Tencomnao T. The effectiveness of Bacopa monnieri (Linn.)

Wettst. as a nootropic, neuroprotective, or antidepressant supplement: analysis of the available clinical data. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):596. Published 2021 Jan 12. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80045-2

39. Peth-Nui T, Wattanathorn J, Muchimapura S, et al.

Effects of 12-Week Bacopa monnieri Consumption on Attention, Cognitive Processing, Working Memory, and Functions of Both Cholinergic and Monoaminergic Systems in Healthy Elderly Volunteers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:606424. doi:10.1155/2012/606424

40. Stough C, Lloyd J, Clarke J, et al.

The chronic effects of an extract of Bacopa monniera (Brahmi) on cognitive function in healthy human subjects [published correction appears in Psychopharmacology(Berl). 2015 Jul;232(13):2427. Dosage error in article text]. Psychopharmacology(Berl). 2001;156(4):481-484. doi:10.1007/s002130100815

41. Roodenrys S, Booth D, Bulzomi S, Phipps A, Micallef C, Smoker J.

Chronic effects of Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) on human memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(2):279-281. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00419-5

42. Delfan M, Kordestani-Moghaddam P, Gholami M, Kazemi K, Mohammadi R.

Evaluating the effects of Bacopa monnieri on cognitive performance and sleep quality of patients with mild cognitive impairment: A triple-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Explore(NY). 2024;20(5):102990. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2024.02.008

43. Valotto Neto LJ, Reverete de Araujo M, Moretti Junior RC, et al.

Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants(Basel). 2024;13(4):393. Published 2024 Mar 25. doi:10.3390/antiox13040393

44. Secades JJ, Gareri P. Citicoline:

pharmacological and clinical review, 2022 update. Citicolina: revisión farmacológica y clínica, actualización 2022. Rev Neurol. 2022;75(s05):S1-S89. doi:10.33588/rn.75s05.2022311

45. Nakazaki E, Mah E, Sanoshy K, Citrolo D, Watanabe F.

Citicoline and Memory Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2153-2160. doi:10.1093/jn/nxab119

46. Alvarez XA, Laredo M, Corzo D, et al.

Citicoline improves memory performance in elderly subjects. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1997;19(3):201-210.

47. Silveri MM, Dikan J, Ross AJ, et al.

Citicoline enhances frontal lobe bioenergetics as measured by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2008;21(10):1066-1075. doi:10.1002/nbm.1281

48. Panossian A, Wikman G, Sarris J. Rosenroot (Rhodiola rosea):

traditional use, chemical composition, pharmacology and clinical efficacy. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(7):481-493. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2010.02.002

49. Mao JJ, Xie SX, Zee J, et al.

Rhodiola rosea versus sertraline for major depressive disorder: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2015;22(3):394-399. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2015.01.010

50. Darbinyan V, Aslanyan G, Amroyan E, Gabrielyan E, Malmström C, Panossian A. Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L.

extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression [published correction appears in Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):503]. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):343-348. doi:10.1080/08039480701643290

51. Pu WL, Zhang MY, Bai RY, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Rhodiola rosea L.:

A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109552. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109552

52. Panossian A, Hambardzumyan M, Hovhanissyan A, Wikman G.

The adaptogens rhodiola and schizandra modify the response to immobilization stress in rabbits by suppressing the increase of phosphorylated stress-activated protein kinase, nitric oxide and cortisol. Drug Target Insights. 2007;2:39-54.

53. Edwards D, Heufelder A, Zimmermann A.

Therapeutic effects and safety of Rhodiola rosea extract WS® 1375 in subjects with life-stress symptoms--results of an open-label study. Phytother Res. 2012;26(8):1220-1225. doi:10.1002/ptr.3712

54. Hung SK, Perry R, Ernst E.

The effectiveness and efficacy of Rhodiola rosea L.: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(4):235-244. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2010.08.014

55. Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Feusner JD.

A pilot study of Rhodiola rosea (Rhodax) for generalized anxiety disorder(GAD). J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(2):175-180. doi:10.1089/acm.2007.7117

56. Koh JH, Kim KM, Kim JM, Song JC, Suh HJ.

Antifatigue and antistress effect of the hot-water fraction from mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26(5):691-694. doi:10.1248/bpb.26.691

57. Savioli FP, Zogaib P, Franco E, Alves de Salles FC, Giorelli GV, Andreoli CV.

Effects of cordyceps sinensis supplementation during 12 weeks in amateur marathoners: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2022;34:100570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2022.100570

58. NAGATA A, TAJIMA T, UCHIDA M.

SUPPLEMENTAL ANTI-FATIGUE EFFECTS OF CORDYCEPS SINENSIS (TOCHU-KASO) EXTRACT POWDER DURING THREE STEPWISE EXERCISE OF HUMAN. Japanese Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine. 2006;55(Supplement):S145-S152. doi:https://doi.org/10.7600/jspfsm.55.s145

59. Ontawong A, Pengnet S, Thim-Uam A, et al.

A randomized controlled clinical trial examining the effects of Cordyceps militaris beverage on the immune response in healthy adults. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):7994. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58742-z

60. Yan G, Chang T, Zhao Y, et al.

The effects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis combined with ACEI/ARB on diabetic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2023;108:154531. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154531

61. Thongbai B, Rapior S, Hyde KD, Wittstein K, Stadler M.

Hericium erinaceus, an amazing medicinal mushroom. Mycological Progress. 2015;14(10). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-015-1105-4

62. Cha S, Bell L, Shukitt-Hale B, Williams CM.

A review of the effects of mushrooms on mood and neurocognitive health across the lifespan. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;158:105548. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105548

63. Szućko-Kociuba I, Trzeciak-Ryczek A, Kupnicka P, Chlubek D. Neurotrophic and Neuroprotective Effects of Hericium erinaceus. Int

J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15960. Published 2023 Nov 3. doi:10.3390/ijms242115960

64. Li MY, Liu HY, Wu DT, et al. L-Theanine:

A Unique Functional Amino Acid in Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) With Multiple Health Benefits and Food Applications. Front Nutr. 2022;9:853846. Published 2022 Apr 4. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.853846

65. Terashima T, Takido J, Yokogoshi H.

Time-dependent changes of amino acids in the serum, liver, brain and urine of rats administered with theanine. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63(4):615-618. doi:10.1271/bbb.63.615

66. Li MY, Liu HY, Wu DT, et al.

L-Theanine: A Unique Functional Amino Acid in Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) With Multiple Health Benefits and Food Applications. Front Nutr. 2022;9:853846. Published 2022 Apr 4. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.853846

67. Baba Y, Inagaki S, Nakagawa S, Kaneko T, Kobayashi M, Takihara T. Effects of l-Theanine on Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Subjects:

A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. J Med Food. 2021;24(4):333-341. doi:10.1089/jmf.2020.4803

68. Hidese S, Ogawa S, Ota M, et al.

Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2362. Published 2019 Oct 3. doi:10.3390/nu11102362

69. Dassanayake TL, Kahathuduwa CN, Weerasinghe VS.

L-theanine improves neurophysiological measures of attention in a dose-dependent manner: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(4):698-708. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2020.1804098

70. Moulin M, Crowley DC, Xiong L, Guthrie N, Lewis ED.

Safety and Efficacy of AlphaWave® L-Theanine Supplementation for 28 Days in Healthy Adults with Moderate Stress: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Neurol Ther. 2024;13(4):1135-1153. doi:10.1007/s40120-024-00624-7

71. Owen GN, Parnell H, De Bruin EA, Rycroft JA.

The combined effects of L-theanine and caffeine on cognitive performance and mood. Nutr Neurosci. 2008;11(4):193-198. doi:10.1179/147683008X301513

72. Kahathuduwa CN, Wakefield S, West BD, et al.

Effects of L-theanine-caffeine combination on sustained attention and inhibitory control among children with ADHD: a proof-of-concept neuroimaging RCT. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13072. Published 2020 Aug 4. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70037-7

73. Kahathuduwa CN, Dhanasekara CS, Chin SH, et al.

l-Theanine and caffeine improve target-specific attention to visual stimuli by decreasing mind wandering: a human functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Nutr Res. 2018;49:67-78. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2017.11.002

74. Fiani B, Zhu L, Musch BL, et al.

The Neurophysiology of Caffeine as a Central Nervous System Stimulant and the Resultant Effects on Cognitive Function. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15032. Published 2021 May 14. doi:10.7759/cureus.15032

75. Pomeroy DE, Tooley KL, Probert B, Wilson A, Kemps E.

A Systematic Review of the Effect of Dietary Supplements on Cognitive Performance in Healthy Young Adults and Military Personnel. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):545. Published 2020 Feb 20. doi:10.3390/nu12020545

76. 1.Marriott BM.

Effects of Caffeine on Cognitive Performance, Mood, and Alertness in Sleep-Deprived Humans.

Nih.gov. Published 2014.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209050/

77. 1.Ruxton CHS.

The impact of caffeine on mood, cognitive function, performance and hydration: a review of benefits and risks. Nutrition Bulletin. 2008;33(1):15-25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2007.00665.x

78. Baba Y, Takihara T, Okamura N.

Theanine maintains sleep quality in healthy young women by suppressing the increase in caffeine-induced wakefulness after sleep onset. Food Funct. 2023;14(15):7109-7116. Published 2023 Jul 31. doi:10.1039/d3fo01247f

79. Dodd FL, Kennedy DO, Riby LM, Haskell-Ramsay CF.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of caffeine and L-theanine both alone and in combination on cerebral blood flow, cognition and mood. Psychopharmacology(Berl). 2015;232(14):2563-2576. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-3895-0

80. Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin:

A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods. 2017;6(10):92. Published 2017 Oct 22. doi:10.3390/foods6100092

81. Peng Y, Ao M, Dong B, et al.

Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin in the Inflammatory Diseases: Status, Limitations and Countermeasures. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:4503-4525. Published 2021 Nov 2. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S327378

82. Rahmani AH, Alsahli MA, Aly SM, Khan MA, Aldebasi YH.

Role of Curcumin in Disease Prevention and Treatment. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:38. Published 2018 Feb 28. doi:10.4103/abr.abr_147_16

83. Spanoudaki M, Papadopoulou SK, Antasouras G, et al.

Curcumin as a Multifunctional Spice Ingredient against Mental Disorders in Humans: Current Clinical Studies and Bioavailability Concerns. Life(Basel). 2024;14(4):479. Published 2024 Apr 5. doi:10.3390/life14040479

84. Tsai IC, Hsu CW, Chang CH, Tseng PT, Chang KV.

The Effect of Curcumin Differs on Individual Cognitive Domains across Different Patient Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals(Basel). 2021;14(12):1235. Published 2021 Nov 28. doi:10.3390/ph14121235

85. Small GW, Siddarth P, Li Z, et al.

Memory and Brain Amyloid and Tau Effects of a Bioavailable Form of Curcumin in Non-Demented Adults: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled 18-Month Trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):266-277. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.10.010

86. Hanna M, Jaqua E, Nguyen V, Clay J. B Vitamins:

Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 2022;26(2):89-97. doi:10.7812/TPP/21.204

87. Depeint F, Bruce WR, Shangari N, Mehta R, O'Brien PJ.

Mitochondrial function and toxicity: role of the B vitamin family on mitochondrial energy metabolism. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;163(1-2):94-112. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2006.04.014

88. Kerns JC, Arundel C, Chawla LS.

Thiamin deficiency in people with obesity. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(2):147-153. Published 2015 Mar 13. doi:10.3945/an.114.007526

89. Via M.

The malnutrition of obesity: micronutrient deficiencies that promote diabetes. ISRN Endocrinol. 2012;2012:103472. doi:10.5402/2012/103472

90. Kennedy DO.

B Vitamins and the Brain: Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy--A Review. Nutrients. 2016;8(2):68. Published 2016 Jan 27. doi:10.3390/nu8020068

91. Ashoori M, Saedisomeolia A.

Riboflavin (vitamin B₂) and oxidative stress: a review. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(11):1985-1991. doi:10.1017/S0007114514000178

92. Amerikanou C, Gioxari A, Kleftaki SA, Valsamidou E, Zeaki A, Kaliora AC.

Mental Health Component Scale Is Positively Associated with Riboflavin Intake in People with Central Obesity. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):4464. Published 2023 Oct 21. doi:10.3390/nu15204464

93. Wu Y, Zhang L, Li S, Zhang D.

Associations of dietary vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 with the risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(3):351-366. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab014

94. Ueno A, Hamano T, Enomoto S, et al.

Influences of Vitamin B12 Supplementation on Cognition and Homocysteine in Patients with Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Cognitive Impairment. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1494. Published 2022 Apr 2. doi:10.3390/nu14071494

95. Luzzi S, Cherubini V, Falsetti L, Viticchi G, Silvestrini M, Toraldo A.

Homocysteine, Cognitive Functions, and Degenerative Dementias: State of the Art. Biomedicines. 2022;10(11):2741. Published 2022 Oct 28. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10112741

96. Ankar A, Kumar A.

Vitamin b12 deficiency. National Library of Medicine. Published 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/

97. Young LM, Pipingas A, White DJ, Gauci S, Scholey A.

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of B Vitamin Supplementation on Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Stress: Effects on Healthy and 'At-Risk' Individuals. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2232. Published 2019 Sep 16. doi:10.3390/nu11092232

98. Kato S.

The function of vitamin D receptor in vitamin D action. J Biochem. 2000;127(5):717-722. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022662

99. Janoušek J, Pilařová V, Macáková K, et al.

Vitamin D: sources, physiological role, biokinetics, deficiency, therapeutic use, toxicity, and overview of analytical methods for detection of vitamin D and its metabolites. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2022;59(8):517-554. doi:10.1080/10408363.2022.2070595

100. Soni M, Kos K, Lang IA, Jones K, Melzer D, Llewellyn DJ.

Vitamin D and cognitive function. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:79-82. doi:10.3109/00365513.2012.681969

101. Casseb GAS, Kaster MP, Rodrigues ALS.

Potential Role of Vitamin D for the Management of Depression and Anxiety. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(7):619-637. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00640-4

102. Plotnikoff GA, Finch MD, Dusek JA.

Impact of vitamin D deficiency on the productivity of a health care workforce. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(2):117-121. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318240df1e

103. Gwon M, Tak YJ, Kim YJ, et al.

Is Hypovitaminosis D Associated with Stress Perception in the Elderly? A Nationwide Representative Study in Korea. Nutrients. 2016;8(10):647. Published 2016 Oct 19. doi:10.3390/nu8100647

104. Almuqbil M, Almadani ME, Albraiki SA, et al.

Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on Mental Health in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare(Basel). 2023;11(14):2097. Published 2023 Jul 23. doi:10.3390/healthcare11142097

105. Sowah D, Fan X, Dennett L, Hagtvedt R, Straube S.

Vitamin D levels and deficiency with different occupations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):519. Published 2017 Jun 22. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4436-z

106. Bowman GL.

Ascorbic acid, cognitive function, and Alzheimer's disease:

a current review and future direction. Biofactors. 2012;38(2):114-122. doi:10.1002/biof.1002

107. Hu X, Yuan L, Wang H, et al.

Efficacy and safety of vitamin C for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2017;37:58-64. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.12.009

108. Sim M, Hong S, Jung S, et al.

Vitamin C supplementation promotes mental vitality in healthy young adults: results from a cross-sectional analysis and a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(1):447-459. doi:10.1007/s00394-021-02656-3

109. Travica N, Ried K, Sali A, Scholey A, Hudson I, Pipingas A.

Vitamin C Status and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017;9(9):960. Published 2017 Aug 30. doi:10.3390/nu9090960

110. Travica N, Ried K, Sali A, Hudson I, Scholey A, Pipingas A.

Plasma Vitamin C Concentrations and Cognitive Function: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:72. Published 2019 Apr 2. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2019.00072

111. Morishima S, Kawada Y, Fukushima Y, Takagi T, Naito Y, Inoue R.

A randomized, double-blinded study evaluating effect of matcha green tea on human fecal microbiota. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2023;72(2):165-170. doi:10.3164/jcbn.22-81

112. Xu L, Wang R, Liu Y, Zhan S, Wu Z, Zhang X.

Effect of tea polyphenols on the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases through gut microbiota. Journal of Functional Foods. 2023;107:105669. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2023.105669

113. de la Rubia Ortí JE, Moneti C, Serrano-Ballesteros P, et al.

Liposomal Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate for the Treatment of Intestinal Dysbiosis in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(14):3265. Published 2023 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/nu15143265

114. Wang J, Xin J, Xu X, et al.

Bacopaside I alleviates depressive-like behaviors by modulating the gut microbiome and host metabolism in CUMS-induced mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;170:115679. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115679

115. Zhu H, Shen F, Wang X, et al.

Reshaped Gut Microbial Composition and Functions Associated with the Antifatigue Effect of Salidroside in Exercise Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2023;67(12):e2300015. doi:10.1002/mnfr.202300015

116. Priori EC, Ratto D, De Luca F, et al.

Hericium erinaceus Extract Exerts Beneficial Effects on Gut-Neuroinflammaging-Cognitive Axis in Elderly Mice. Biology(Basel). 2023;13(1):18. Published 2023 Dec 28. doi:10.3390/biology13010018

117. Xie XQ, Geng Y, Guan Q, et al.

Influence of Short-Term Consumption of Hericium erinaceus on Serum Biochemical Markers and the Changes of the Gut Microbiota: A Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):1008. Published 2021 Mar 21. doi:10.3390/nu13031008

118. Wang J, Mei L, Hao Y, et al.

Contemporary Perspectives on the Role of Vitamin D in Enhancing Gut Health and Its Implications for Preventing and Managing Intestinal Diseases. Nutrients. 2024;16(14):2352. Published 2024 Jul 20. doi:10.3390/nu16142352

*This research was privately conducted and has not been evaluated by the FDA. No control group was used. Results may not be generalizable.